Sweating and sleepwalking into the Wonderbus Festival gates just as they opened in Columbus, Ohio, in late August, I was excited. Trying to fast forward to the part of the day when I was to steal some time from Anthony Watkins II, a.k.a. Mobley, for a portrait. When that time came, his tour manager, Dani, and I found a discreet location near the Olentangy River behind a gaggle of food booths for me to set up. Once ready, Mobley and Dani joined me via golf cart among the trees for a quick, 10-minute shoot.

Before meeting Mobley, you can gather what kind of person he is just by listening to his music. He’s gracious, confident, passionate and driven— there’s no mistaking it for anything but pure genuineness. No disappointment. He showed up in a skull cap with a chevron mesh knit shirt and burgundy pants accented with a white belt—fresh.

I had a few questions I wanted to throw his way as well. But with he and his tour manager driving straight from Austin to Columbus, Covid restrictions, and his hour slot sandwiched between Grandson and AJR, it was better to get ahold of him after the festival. He answered questions while driving through Utah on route to Portland to open for Lewis Del Mar, thankfully after he had a run-in with a buck.

“I haven’t been on the road in probably two years,” he said. “I really haven’t been in a van touring since the Fall of 2019, and here we are on the cusp of Fall 2021.”

Peppered with highway reverb and the occasional blinker, Mobley rationalizes the name Mobley: “It’s kind of hard to explain, but the short version is it came to me in a dream. It’s really abstract and difficult to describe a dream, but it came to me in a dream.”

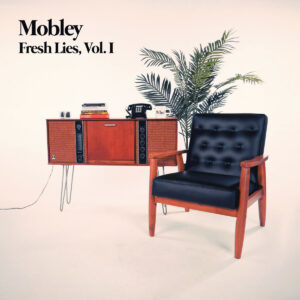

Much like the complicated origins of his name, fastidious lyrics are rooted in the most basic struggles of the human condition, love, love-loss and compassion frothed on top of luscious danceable grooves and relentless bass lines. He’s been a staple of the Austin scene for years, but made the splash with his 2019 album, Fresh Lies Vol. 1, propelling him from a gentle nudge of “hey, this guy is good” to a smack-on-the-back-of-the-head awakening before blowing your mind. Fresh Lies is a near flawless album. I’d list tracks, but the intricate flow is a trust-fall that lands perfectly together like holding hands for the first time with your first crush. Yeah, it’s like that.

Sojourning in Thailand in 2018, Mobley contemplated his next album, Young & Dying in the Occidental Supreme and much like 2020, it’s all over the place in comparison to Fresh Lies, where each song stands on its own.

“I wrote this record before the pandemic and the main story at the time was family separation at the border, and I was thinking about the myths that people in the US like to believe about our country and ourselves: the greatest nation in the world, so on and so forth,” he said.

He expanded on the new album, “Kind of observing what was happening from not only the United States, but also outside of the larger ‘West’ was really morally clarifying. On the news, instead of saying the kind of politically sanitized version that we would get on our news here, they would just say, ‘the United States is committing human rights abuses against asylum seekers at its southern border.’ And so that moral clarity with which the manufactured crisis was being addressed was refreshing, and I kind of wanted to adopt that same moral clarity in the work I was making.”

On the track “James Crow,” a relatable phrase to his time in Thailand is ushered in quite quickly:

“But then I noticed that I’d been watching myself

from the car outside

And so to bring me round

I took me down a long dark ride”

He explains: “That’s a roundabout way of saying Young & Dying in the Occident Supreme was kind of a way of challenging this idea of the cultural supremacy of the so-called West by pointing at all of the unnecessary death and suffering that happens here, not just among asylum seekers but people languishing in prison, people who are unhoused, people that don’t have healthcare, people for a variety of reasons that don’t have access to the bounty that’s available to the richest country in the history of the world. So, that’s what the title’s about.”

- Fresh Lies, Vol. 1

- Young & Dying In The Occident Supreme

There’s no getting past the symbolism in “James Crow,” and the catchy pop-rock backing helps along the point Mobley is trying to get across—in laymen’s terms— systems of social, economic, and artistic oppression against African Americans. As a black artist in a turbulent time of Black Lives Matters vs. Proud Boys and MAGA fans, is it off-the-cuff songwriting or more of a difficult approach?

“For me it’s difficult not to. I’ve always had an easier time writing about the things that hurt me the most and the things that make me the most angry. I was fortunate enough to grow up in an environment where [those things included] believing I had fallen in love and relatively speaking, pretty minor small stuff. So, as a teenager when I first started writing music, I wrote a lot about that.”

He continued, “As I’ve gotten older, more and more the things that occupy my mind, inflame my passions are questions about what we are going to do as a society, as a species whether we are going to show any interest in taking care of each other. Any interest in improving conditions for those of us who are getting the short end of the stick in a variety of ways right now. It feels impossible not to write about it at this point.”

Brandished by critics as the EP’s hit track, there’s more to it than “James Crow.” Dive into “Nobody’s Favourite” and the psychedelic dreamscape track, “Mate.”

“I write about other things as well. There’s a song called, “Mate” on the record, which is about falling in love, and I think it’s important for me in particular, but I think for people in general to ground everything in love. I think at the end of the day, the things that enrage me, the things that injure me do so either because they interfere with my own desire to be loved and accepted in a basic human way or they interfere with the people who I love,” he said firmly.

“At the end of the day I think everything is grounded in love, it’s just not always a romantic love. Sometimes it’s more about that human fellow feeling and basic love and concern for the dignity of other people who I share this planet with,” he expressed.

The humanistic approach to Mobley’s music writing is evident, and during his slot on the RADD stage at Wonderbus, he got the crowd involved on and off stage. He gave voice lessons on how to project and festival-vetted a foursome of volunteers to execute his “human drum machine” in the middle of his set. Being a one-man band jumping from keyboards to a sampler to a drum kit while playing guitar and singing—why not add another thing?

He lays it out for the crowd: “For people who haven’t seen me before, I’m the only person on stage—I play guitar, sing, bass, drums and this machine I built called the ‘human drum machine,’ which I hook people up from the audience to and touch their hand to play them as an instrument.”

“I think I saw that a company had a product that was marketing to kids where you could use this microchip platform that lets you write programs to run off these preconfigured boards that you can add functionality to,” he added. “But, the children’s version they made allowed kids to hook pieces of fruit or coins up to this board using banana clips and use those to trigger midi sounds.”

“When I saw that, I had a thought: well, fruit is mostly water and people are mostly water and I bet I could do that with people. Obviously, you don’t want to be clipping banana clips to people, so I built my own version that uses copper tubes connected to wires that plug into the chip board, built my own enclosure for it and then wrote custom software that integrates with my show really well.” Excitedly, he concluded, “It’s been really fun developing it and getting to see people enjoy being part of the show, being an instrument and disbelieving it as it’s happening.”

With such an array of electronic components, there was one thing missing from his midday set that he’s known for in an inside venue: a visual component.

“I think [the visual component] is important in that art is very much about shaping the way that the audience receives your message. So, most of my shows are club shows. I like to turn off all the lights, control what’s being illuminated, I like to control the colors they are seeing, the images they are seeing, evoke feelings and ideas that I want them to be sitting with while they’re encountering my music. In that regard, it’s really important.”

Being your own band and producer without a label biding over your work making sure it’s commercially viable and describing yourself as “post-genre pop” not really fitting into a genre or weaving your way through genres is a task. This characterization is pigeonhole-less in an industry that wants to pigeonhole you.

“Creatively, it’s really empowering. When I’m writing I don’t really worry about how a song might be marketed or the way it fits in with the music I’ve made before from a genre standpoint,” he said.

“I think it possesses challenges, especially being black and making music in spaces where people aren’t used to marketing black people or to them. It’s certainly a career challenge for me. But, I just make the music that I love and count on the fact that there are a lot of other people out there like me who will like the things that I like and like the things that I like to make.”